Art, Culture, Country

Partnering with remote Indigenous Art Centres to deliver a landmark digital project that empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to create and share unique arts and cultural experiences with the world.

Art, Culture, Country

Partnering with remote Indigenous Art Centres to deliver a landmark digital project that empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to create and share unique arts and cultural experiences with the world.

Art at the Centre of Community

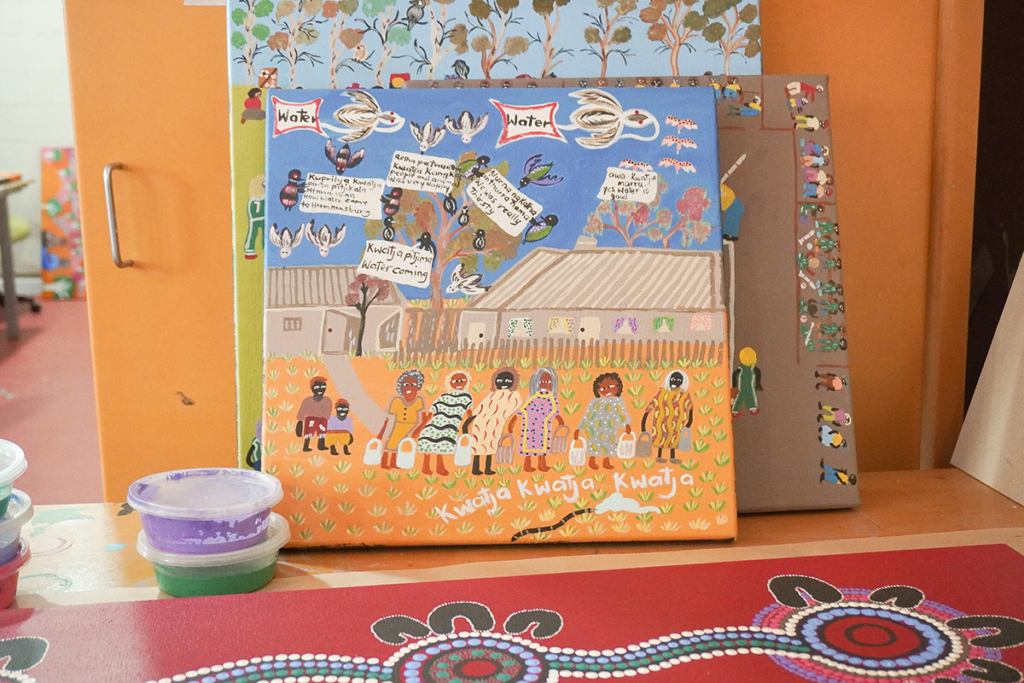

Song rings out through the art centres as an Elder sings the story of the Country they are painting, renewing their Country while teaching the story to any in earshot; sometimes when this happens people join in. Kids, grandkids and great-grandkids listen, if not learning with intent learning by just being there. This is how culture is maintained, how we will have culture forever; whenever the story is told or sung it’s renewed. This, as much as the incandescent art we all think of, is what an art centre is; a place where culture is maintained and where Indigenous people can be safe to practice and maintain culture.

If you have never been to an Aboriginal art centre, even if you love Aboriginal art, you might have no idea what they are or what they really do. Art centres have a presence pretty much anywhere you find Indigenous artists, particularly in fourth world areas where people experience abject poverty despite being in a wealthy country. Art centres work to provide economic opportunities for Indigenous people but they are more than that, they strengthen and empower culture and keep people safe and healthy in a racist colony.

Having lunch at the weekend Courthouse Markets in Rubibi (Broome) I was interrupted by an Aboriginal man walking from table to table attempting unsuccessfully to sell a carved boab nut. They are collectable items but it can be rough watching people desperately trying to sell their beautiful carvings, and being constantly rejected.

It is self-evident that there’s a class issue at hand. Indigenous art is often devalued because the buyers often don’t consider the artist’s time to make work worth paying for. The class and privilege imbalance leads to what is called a ‘carpetbagger’ in Aboriginal English; an unscrupulous art dealer who abuses Indigenous artists for profit. There are horror stories all through the history of Indigenous art, of dealers locking up artists until they make enough art, of insane mark-ups for art, of intimidation and abuse. I have personally observed an art dealer in his painting shed (who did not know who I was) intimidating an artist, an older woman, out of leaving.

I have been told a story of an artist being paid for a painting with cheap mince and a six pack of beer.

An art centre, which can come in many forms and almost infinite organisational structures, is another way.

In the industrial area of Rubibi you can find Nagalu Jarndu (meaning “Saltwater Women” in language) an art centre and social enterprise that specialises in textile design. Founded a generation ago by Yawuruwomen, the traditional owners, they welcome all Indigenous women who live in town. Its a safe place for Indigenous women and has always been a place where they can do art and be financially independent.

It is typical for artists at art centres to have more control of their affairs, they are almost entirely community run and most have Indigenous boards of directors (although many have non-Indigenous support staff and volunteers). In addition it is normal for the artists at art centres to receive 60% – 70% of the sale price of their art, a fair price set by the centre. What money is left is mostly used for operational costs and for special projects like trips to Country such as the trip that famously led to the Ngurarra II canvas.

About 400 kms inland from where I sit, in the central Kimberley, is the town of Martumurra (Fitzroy Crossing). There was a population explosion at Fitzroy when Aboriginal people from all around the region were kicked off stations by owners who refused, after the advent of equal pay, to pay them the same as the white station hands. It’s a relatively poor town, with a high proportion Aboriginal population, of people from all around the region. It is the hometown of Mangkaja Arts whose mission statement is: “Mangkaja Arts supports culture through the maintenance, documentation and sharing of traditional cultural knowledge and activities while providing employment and training opportunities for Aboriginal people in the region.”.

In 1997 a group of artists from Mangkaja Arts held a painting camp on Country, and there collaborated on a 10 m by 8 m painting called the Ngurarra II Canvas. This canvas, a map of the soaks and waterholes on their sacred Country, was to be entered as evidence for the landrights claim for the country it represented. This work of art was considered to be documentary evidence of ownership of and connection to country and was instrumental to the artists winning their land back. They celebrated, as can be seen in the Nicole Ma’s documentary film Putupari and the Rainmakers, by each artist standing on the rolled-out canvas on the representation of their country.

This is just one of many examples of projects by art centres that have had a reach far beyond just making art. In many communities, art centres are pivotal in the provision of health services, they maintain museums and keeping places, they run digital projects like Buku Larrnguy Mulka art centre’s Mulka Project to preserve stories, songs and dances, and they provide employment on Country for Indigenous people.

Art centres are the centre of culture in the communities they represent, bringing together artists and the community to strengthen and maintain culture; while creating economic opportunities and community services. Visiting and supporting an art centre, volunteering at an art centre of even just buying a work of art that you love is perhaps the best thing you can do to help Indigenous communities. And that is what really matters.

Claire G. Coleman is a Noongar woman whose family have belonged to the south coast of Western Australia since long before history started being recorded. She writes fiction, essays, poetry and art criticism while either living in Naarm (Melbourne) or on the road.

UPLANDS is an immersive digital project that has been designed to celebrate Indigenous Art Centres and share Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artistic and cultural practices with the world.

This large scale immersive digital mapping project features over twenty remote Indigenous Art Centres, and interviews with over 150 Indigenous artists and arts workers from across the country.

UPLANDS is a project by Agency and has been funded by the Australian Government through the Restart to Invest, Sustain and Expand (RISE) program and the Indigenous Visual Art Industry Support (IVAIS) program.

Government Partners

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Sovereign Custodians of the land on which we live and work. We extend our respects to their Ancestors and all First Nations peoples and Elders past, present, and future.