Art, Culture, Country

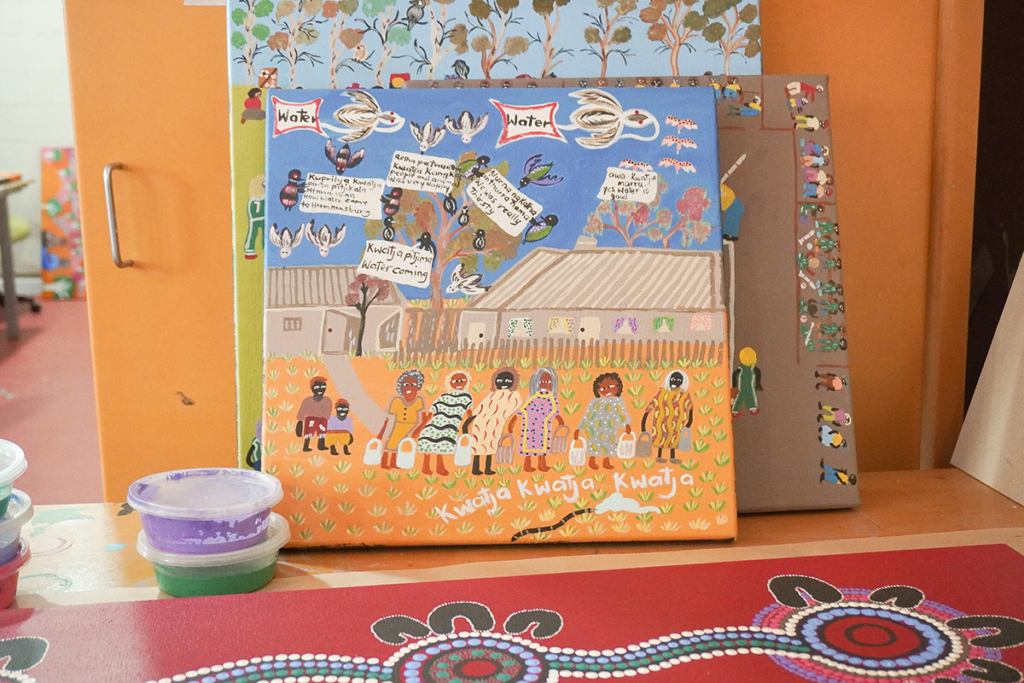

Partnering with remote Indigenous Art Centres to deliver a landmark digital project that empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to create and share unique arts and cultural experiences with the world.

Art, Culture, Country

Partnering with remote Indigenous Art Centres to deliver a landmark digital project that empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to create and share unique arts and cultural experiences with the world.

Mapping and unmapping understanding through Uplands

Distance. Outlines. Boundaries. Maps give us context between places. Yet they exist in tension with the way that First Peoples understand kinship and country. Our mapping is alive and relational. It’s something we practise, with questions like “who’s ya mob?” or “where you from?”. We want to get a sense of your belonging. And in First Nations contexts, those connective lines aren’t drawn on a page. They are through skin and songline. Cultural knowledge and understanding. Boundaries are respected through ceremony. Tended to, not fought over.

Maps, especially digital ones, have followed me through my career, offering a way to understand distance and closeness. Although they have origins in colonial explorations, from the navigators who thought little of taking lands from the people who they found there, these devices have become tools that help people understand the diversity in Aboriginal arts practices across the country. For me, Uplands represents a long overdue resource for the sector, that enables artists and communities to share sights, sounds and textures from their Country, free from the motivations of an arts institution.

In my work as a digital producer for Museum of Contemporary Art and at Sydney Opera House, my curatorial colleagues grappled with the idea of communicating scale and distance with audiences new to Aboriginal art and communities, particularly from remote areas. Presenting artworks from these areas in national or state institutions can sometimes flatten the significance of place. The white cube of an art museum sometimes compromises the relationality, complexity and context of Aboriginal artists’ work. We had many discussions about how to tell stories of the artists, about their process and home Country. Some of the key projects I worked on were interactive, touchscreen offerings that allowed audiences to sink further into the world of the incredible First Nations artists in their exhibitions.

This began in 2015, when I created a digital resource for Wiradjuri artist and curator Nicole Foreshew’s Primavera. Featuring artists from the global south, the graphic designers of the exhibition devised a wandering linear graphic to plot an invisible trajectory that connected the artists in the exhibition. I had lots of conversations with Nicole at the time about the idea of mapping: how it was a tension between old and new ways of connection. A map pinning these artists’ locations could never hold the same weight from a First Nations perspective–though it poetically echoed songlines and energetic throughlines within their practices–but we knew Western mapping is in some ways the only method we have to indicate custodianship, territory and belonging. We created something that provided context, yet it was limited.

The idea of distance came up again on the next project I created for the museum: a digital resource featuring artists from Tiwi Islands for the exhibition Being Tiwi. As part of the development for the resource, I went on a research trip to Tiwi Islands with the curatorial team. The aim was to reference the long history of printmaking, the different art centres on the island, highlighting artist voice with video interviews and audio of key Tiwi words in the exhibitions.

It was part of the exhibition design, too, to show how far Tiwi was from Sydney. I don’t know if there’s something colonial about the idea that people need to relate things back to a context that they understand–eg a “city” as they know it–or if it’s just a part of being human, wanting to relate it back to the personal. How are we the same, how are we different. How can I understand you, if I don’t understand where you’re from?

We spent 5 days on Tiwi Islands, visiting Jilamara Arts & Crafts, Munupi Arts & Crafts and Tiwi Design, so curators Keith Munro and Natasha Bullock could spend some time with the artists and art centre managers, and so my colleague and I could meet and yarn with some of the artists. The trip opened my eyes to the variety of perspectives and experiences of Aboriginal artists practising across their nations and gave me profound new context for the lands that I am from in Western Victoria. I’m proud of what we created for the exhibition too: video, audio and text on a touch screen resource that accompanied the exhibition on its tour across Australia.

In my work, I noticed a hunger to understand more about how artists create work and get a sense of their communities. Thinking back to the conversations we had in programming meetings about how to share story and provide gallery visitors an understanding of Aboriginal art and how it relates to place, I can’t help but wish we’d had Uplands at our fingertips. We needed Uplands not just because it gathers artist interviews from specific communities, but how they are simply presented alongside their neighbours, all speaking for themselves. Allowing artists to speak in their own distinct voice and share varied experiences, alongside one another, gently shows the breadth and complexity of Aboriginal arts practice across the Country. It’s another part of our self-determination and sovereignty to talk about ourselves in our own words.

I’m sure that these searching conversations continue between curatorial leads in galleries across Australia, or in gallery education teams, art faculties at universities or between high school art teachers.

Watching the Uplands videos of Timothy Cook and Pedro Wonaeamirri speaking in Jilamara Arts & Crafts reminds me of the feeling I got during my visit to their Country. These men have such pride for their work, community and story. They create in a completely ego free way. I remember wrapping my head around the fact that these artists from a little island community are award-winning and internationally collected. From brilliant artist Timothy Cook, whose stunning circular kulama designs hypnotically beckon in the footage, to the stately Pedro Wonaeamirri, whose delicate and fine works painted with the pwotja comb on bark and pukumani are in stark contrast to Cook’s. Then there are the printmakers of Tiwi Designs, whose international ascendance began in 1970s, just showing the diversity and skill of artistry on this small strip of land. Not to mention the wood carvings. Just as I uncovered the richness of arts practise from this community, so too can others through Uplands.

From Tiwi to Martumili, Shepparton to Arnhem Land and you’ll have a completely different experience from place to place, because Aboriginal artists respond so keenly to their surroundings. It’s a chance to see the varied methods of art-making and storytelling. It’s an opportunity to dig deeper into the nuances: you won’t see a monolith or one way of looking at the world. There might be commonalities, but at best you’ll come to understand a shared pace. Pace of people who don’t go at the pace of South-Eastern Australia or metropolitan areas. You might start to understand a new way of looking at things.

These little orange pins represent tiny communities spanning many nations, all home to fine artists, developing a contemporary practice to continue the culture they have nurtured for thousands of years. Across form and place, a rich diversity of cultures is represented on the map. A map which is essentially just lines, ephemeral across the surface of the land. It’s a way in, a representation of connections that go deep, deeper than Western understanding.

Wergaia and Wemba Wemba writer Susie Anderson’s poetry and non-fiction writing about art, artists, memory, place and love has been published widely in print and online. Her debut poetry collection the body country is an outcome of the State Library of Queensland black&write! Fellowship and was published with Hachette in 2023, available now. Susie grew up in Horsham, Victoria and is currently based on Boon Wurrung land.

UPLANDS is an immersive digital project that has been designed to celebrate Indigenous Art Centres and share Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artistic and cultural practices with the world.

This large scale immersive digital mapping project features over twenty remote Indigenous Art Centres, and interviews with over 150 Indigenous artists and arts workers from across the country.

UPLANDS is a project by Agency and has been funded by the Australian Government through the Restart to Invest, Sustain and Expand (RISE) program and the Indigenous Visual Art Industry Support (IVAIS) program.

Government Partners

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Sovereign Custodians of the land on which we live and work. We extend our respects to their Ancestors and all First Nations peoples and Elders past, present, and future.