Art, Culture, Country

Partnering with remote Indigenous Art Centres to deliver a landmark digital project that empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to create and share unique arts and cultural experiences with the world.

Art, Culture, Country

Partnering with remote Indigenous Art Centres to deliver a landmark digital project that empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to create and share unique arts and cultural experiences with the world.

Watercolour Country

Across Aranda Country, the continuation of culture through art making is alive and ongoing.[1] Guided by the teachings of ancestors and kin, and a resounding urge to depict Country in the manner of those who came before, contemporary watercolourists have ensured that the ‘Hermannsburg School’ continues to inspire and connect artists across Central Australia. On display at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia until 14 April, Watercolour Country: 100 works from Hermannsburg celebrates this movement’s thriving legacy.

Established in 1877 nearby the populous Aranda Community of Ntaria, Hermannsburg was the first Aboriginal mission in the Northern Territory. Carpeted in spinifex, the settlement nestles between Tjoritja (MacDonnell Ranges) and Uruna Tjina (James Ranges). Corkwood, mulga and desert oak trees provide shade during summer’s extreme temperatures, while Lhere Pirnte (the Finke River) offers water when the rains allow. Deep canyons and gorges traverse this Country, home to throngs of red cabbage palms brought to the area from Boodjamulla (Lawn Hill) by First Nations peoples over 30,000 years ago. The hearts of the young trees are edible when properly cultivated, their leaves dried and used in weaving practices. Like the paintings it would come to be known by, Ntaria is vibrant and richly hued, dotted with ghost gums reminiscent of the white heat felt in the air, while the ancient, often-dry riverbed radiates a near-crimson glow. The intensity and dynamism of Aranda Country is tangible in the work of the watercolourists.

While depicting Country through watercolour is embraced by contemporary artists, its roots come from the pioneering work of a single painter, Albert Namatjira. Widely considered one of Australia’s most important artists, Namatjira nurtured his own style of painting after developing a friendship with travelling Melbourne-based artist, Rex Battarbee. In 1936, Namatjira and Battarbee embarked on a two-month painting expedition around Mpurlangkinya (Palm Valley) and Tjoritja, Namatjira acting as Battarbee’s guide to the landscape he so profoundly understood. It was on this excursion Namatjira learnt the techniques of watercolour which eventually became his craft.

From the late 1930s, Namatjira’s practice was receiving great attention, and his engagement with Western painterly techniques became the focal point for critics. At the time, his watercolours were celebrated as symbols of ‘successful cultural assimilation’, in line with the violent colonial policies of the era. Before long, Namatjira had become an internationally renowned celebrity. To help navigate the influx of finances gained from the sale of his paintings, in 1957 the artist became the first Indigenous person awarded Australian citizenship, followed shortly after by his wife, Rubina. The ‘privilege’ of citizenship was granted to Rubina in order to re-legalise her marriage to Namatjira – suddenly an unlawful union between an Australian citizen and an Indigenous woman. The couple’s citizenship allowed them access to home ownership, a rite previously unafforded.

Suddenly, the couple were caught between two worlds and expected to abide by the often-conflicting rules of societal law and cultural lore. There was no greater example of this conflict than when, a year later, Namatjira was charged with supplying alcohol to his close friend and artist Henoch Raberaba, an action illegal in settler society but expected under Aranda lore, which insists that one shares what they have among kin. Namatjira was charged with providing alcohol to an Aboriginal person and served two months in prison. He was released a free but broken man and was desperately unwell after his incarceration. Namatjira died of heart failure just three months later.

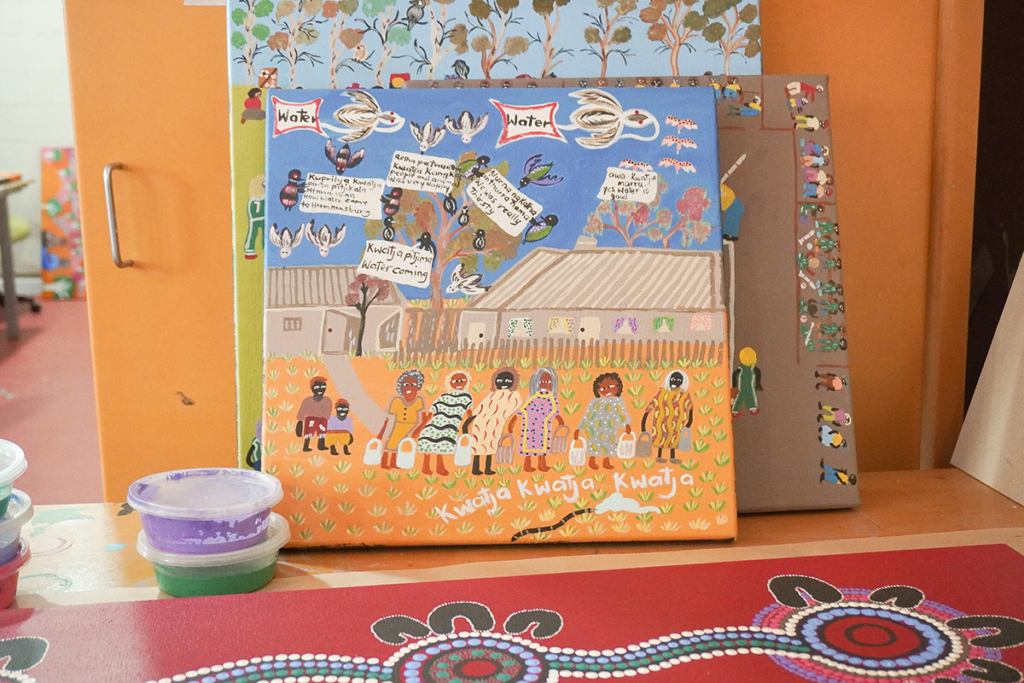

Eighty-five years on from Namatjira’s first exhibition in 1938, the land around Ntaria has witnessed profound change. However, despite the time passed, the traditions and teachings of Namatjira remain warmly constant. Today, most artists working in this manner are based in Mparntwe, and practice at Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre. At a glance, the heritage embedded within contemporary paintings is unmistakable, however in reality, those produced today are also incredibly modern and fresh, incorporating innovative styles and motifs that ensure their continued relevancy. Among Iltja Ntjarra’s artists, Benita Clements, Dellina Inkamala and Reinhold Inkamala are embracing new ways of depicting Country, with the incorporation of text, figures and man-made objects allowing them to construct satire and political messages into their practices. Clements’ painting McDonalds Ranges 2016, for example, shows Blackfellas hunting for bushtucker, almost eclipsed by the prominent M logo: a play on the colonial name for Tjoritja – ‘the MacDonnell Ranges’ – and a nod to the stampeding industrialisation of Country.

Alongside innovation in subject matter, artists are also experimenting with new materials, branching from the singularity of watercolour. Fashion has been a key focus for the Centre in recent years, with artists showcasing their first hand-painted fashion line at Darwin’s 2023 Country to Couture runway, before heading to the catwalk for the 2024 Melbourne Fashion Festival. Meanwhile, many artists are repurposing discarded road signs and car parts for their painting supports, while others are working with fabric, integrating pen, acrylic paint and graphite into their compositions. Woven in time 2022 is a collaborative work, produced by eleven women at the Centre: Selma Coulthard, Vanessa Inkamala, Kathy Inkamala, Dellina Inkamala, Betty Namatjira, Benita Clements, Dianna Inkamala, Delray Inkamala, Mandy Malbunka, Bronwyn Lankin and Tina Malbunka. Composed on five silk panels, the works weave stories from the artists’ life on Country. Happy memories are depicted, alongside nightmares and painful pasts. On a recent visit to Melbourne, artist Dellina Inkamala unpacked the imagery within her own section of the work, which shows the negative effects alcohol had on her youth. Like many young artists working at Iltja Ntjarra, Inkamala credits her practice, along with the community, connection and financial support that painting brings, to the fulfilment of her life today. Inscribed on her panel, Inkamala writes, ‘I was wasting my life. So I made changes. I started doing things I really liked which was painting, telling stories through my painting. I’m feeling stronger and more confident with myself now.’

In 2017, Iltja Ntjarra began a new chapter in their history with the launch of the Namatjira Legacy Trust, begun by two of Namatjira’s granddaughters, Lenie Namatjira and Gloria Pannka. Working to secure funds for better housing, education and the continued teaching of watercolour, the Trust is a grass roots organisation with the key mission to support Culture and Community. In its inaugural year, the Trust secured the transfer of copyright funding for Namatjira’s watercolours back to his descendants. The Namatjira family had not received any finances for the copyright since it was sold to a non-Indigenous art dealer in 1983.

‘The most important thing to our family is keep our culture strong…We are hoping that the Trust will help us to achieve better living conditions for our families, better schooling for our kids, and better resources for our art centre. We want to run the buses out and pick up the kids after school, and take them to paint on the country that we learnt to paint on from our fathers.’[2]

The Hermannsburg school stands as a bridge between past and present, and is a living testament to the enduring spirit of culture and artistry. And while engrained with a rich and moving past, artists and the dedicated workers at Iltja Ntjarra work to ensure that the movement’s history is paralleled by its promising and dynamic future.

[1] There are various spellings of Aranda Country, including Arrernte and Arrarnta. For the purposes of this essay and the exhibition, the spelling ‘Aranda’ has been adopted after consultation with artists at Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre.

[2] The Namatjira family, https://www.namatjiratrust.org/

Sophie Gerhard is Curator of Australian and First Nations Art at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) and curator of Watercolour Country.

UPLANDS is an immersive digital project that has been designed to celebrate Indigenous Art Centres and share Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artistic and cultural practices with the world.

This large scale immersive digital mapping project features over twenty remote Indigenous Art Centres, and interviews with over 150 Indigenous artists and arts workers from across the country.

UPLANDS is a project by Agency and has been funded by the Australian Government through the Restart to Invest, Sustain and Expand (RISE) program and the Indigenous Visual Art Industry Support (IVAIS) program.

Government Partners

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Sovereign Custodians of the land on which we live and work. We extend our respects to their Ancestors and all First Nations peoples and Elders past, present, and future.